This is part two in a series about writing rhyming picture books. Read part one to learn about the kinds of books that work well in rhyme, how to form a perfect rhyme, and whether it’s true that the publishing industry is anti-rhyme.

In a picture book, where there’s rhyme, there’s metre. Whether you’re writing in rhyming couplets or a different rhyme scheme (e.g. ABCB), your readers will be unconsciously expecting you to use metre to guide them from one rhyme to the next.

What is metre?

The metre (or meter, in American English) of a poem is its rhythm. More specifically, it’s the pattern and number of stressed and unstressed syllables that give a poem or story its distinctive cadence.

If the idea of following a metre seems daunting, know that you’re probably more familiar with the idea than you think you are. Take a look at the following poem:

There once was an author from Boston

whose books people always got lost in.

She wrote on her yacht. Then one day, she thought . . .

What’s next? You can feel it, can’t you? daDUM dadaDUM dadaDUM da.

In a limerick, the first, second, and fourth lines follow the same metre, so even if you don’t know the next line, you can anticipate what it’s going to sound like. (I made up the start of this limerick as an example, so if you have an idea for a great last line, post it in the comments!)

Just like in a limerick, the metre in a picture book acts as a road map for the reader. There are a few different ways to approach metre (stay tuned for part four of this series!), but for now, we’ll stick to the basics.

You may recall from English class that Shakespeare wrote in iambic pentameter. Let’s break down what that means:

Iambic refers to the stress pattern. An iamb is a foot (the unit that gets repeated in the metre) consisting of an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable: daDUM

Pentameter refers to the number of feet in a single line. The prefix penta- means five, so in iambic pentameter, the iamb (daDUM) gets repeated five times: daDUM daDUM daDUM daDUM daDUM.

By combining the elements above, you can create a metre that follows a clear pattern. Here are some examples you may recognize (both are in the public domain):

Iambic tetrameter (daDUM x4)

Beware the Jabberwock, my son!

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!

(“Jabberwocky,” from Lewis Carroll’s Through The Looking-Glass.)

Anapestic tetrameter (dadaDUM x4)

’Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house

Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse.

(“A Visit from St. Nicholas,” attributed to Clement Clarke Moore.)

Each metre creates a different effect. Where an iambic metre can be conversational or even metronomic, an anapestic metre frolics and races along. Once you know what you want to write, the next step is to make sure your text fits your metre. That’s where stress comes in.

Understanding Stress

English is a stress-based language. That means that certain syllables are said with more emphasis than others. Sometimes changing the stress is merely a pronunciation error (e.g. saying greater instead of greater), but sometimes it can change the meaning of a word (e.g. produce vs. produce). In a rhyming picture book, getting the stress right requires two steps.

1. Consider the natural stress pattern of each word

What’s wrong with the line below?

Not a creature was awake, not even a mouse.

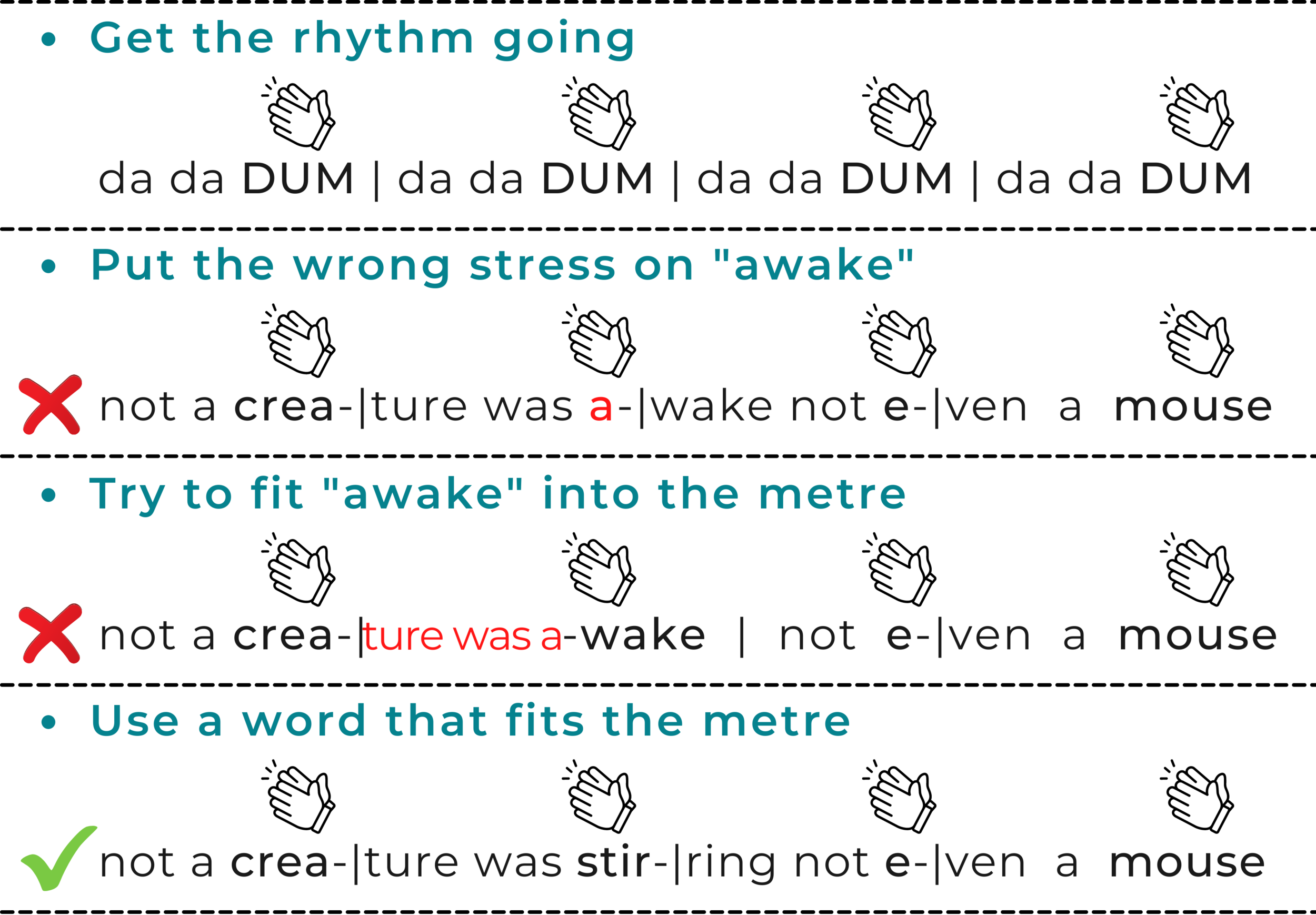

The word “awake” is pronounced with the stress on the second syllable. The line above has an anapestic metre (dadaDUM), so the stress is on every third syllable. To make the line work, you have two less-than-ideal choices:

Put the stress on the wrong syllable to fit the metre:

not a creature was awake, not even a mouse

Pronounce each word naturally and stumble over the extra unstressed syllable:

not a creature was awake, not even a mouse

Solution: change “awake” to a word that has the stress on the first syllable:

not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse

If the problem there is hard to see in writing, try clapping out a four-beat pattern like a metronome. In the first example, you’ll hear how you have to reverse the stress on “awake.” In the second example, you’ll see that you have to speed up between “creature” and “awake” to fit in all the syllables.

2. Consider the natural stress of the phrase

There’s a hierarchy to word stress. For example, nouns and verbs usually receive more stress than prepositions, conjunctions, and articles. Sometimes changing the stressed word in a sentence sounds unnatural. Sometimes it can change the implied meaning of the sentence:

I want to go to the library. (Implied: No, she doesn’t; I do!)

I want to go to the library. (Implied: I really do!)

I want to go to the library. (Implied, for example: Not just drive past it.)

I want to go to the library. (Implied, for example: Not the park.)

Try to read this rewritten line from “Jabberwocky” in the poem’s iambic metre (daDUM daDUM daDUM daDUM):

Beware the Jabberwock, my son!

Its jaws bite, and its claws can catch!

In the second line, each word has only one syllable, so it may seem like they should all fit the metre. But look at the way the stress falls: its jaws bite, and its claws can catch. The word “and” shouldn’t be stressed more than “bite.”

Compare to Carroll’s real line:

“The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!”

Can you hear how much more natural that sounds?

Stressing over syllables?

You’ll find some people who say counting syllables is the wrong approach to writing in rhyme, and that stressed beats are what matter. I disagree. Only counting syllables is the wrong approach. (Think back to the “Jabberwocky” example above: my version still had eight syllables in the second line, but it didn’t work with the metre.)

Similarly, only counting stressed beats can cause problems. Anapestic tetrameter (dadaDUM x4) and trochaic tetrameter (DUMda x4) both have four stressed beats, but readers would almost certainly stumble if you accidentally put a trochaic line into an anapestic story.

It’s all about balance, and understanding what your metre is will help you use it more effectively.

As the saying goes, you have to know the rules to break them. If you’re struggling with metre, take some time to get comfortable with the basics. When you’re ready, you’ll be able to get creative about varying your metre in different ways.

Next Steps

In part three, I’ll give you five practical tips to make your rhyming picture book as strong as it can be.

Using metre effectively can be hard, but an editor who specializes in rhyme can help you smooth everything out for your reader. When you’re ready, let’s talk about how I can help you refine your rhyme and metre.

Read More

Rhyme & Metre Series – Part 1: So you want to write a rhyming book

Rhyme & Metre Series – Part 3: 5 easy ways to improve your rhyming picture book